Recently, I discovered a very nice blog post by Leo Cavalcante about trying to capture some musical concepts in F#: Music with F#: The Language and the Note. This prompted me to experiment a bit on my own. What follows is a slightly chaotic record of me trying to capture some basic concepts of music theory in the F# type system. The ultimate goal of this exercise was to devise an easy way to generate chord progressions for any key and mode/scale and export them into Sonic Pi.

By a fortunate coincidence, it turns out this is not the only post about this topic in this year's advent calendar! Be sure to check out Christophe Moinard's great series on Music Theory in F#!

A Short Disclaimer

The first thing to note is the definition of "Music Theory" that I'm applying here. For many Westerners, the "rules of music" that we learned or heard about are treated as The Music Theory. As many may suspect though, there are no iron-clad rules to music. Globally, you can see countless examples of music that does not adhere to this golden standard of "how music works". Adam Neely made an excellent video about this: Music Theory and White Supremacy and suggests a more fitting name might be: "The harmonic style of 18th-century European musicians." All this to say that, while I will be using some terminology that comes from that style, it is mainly because that's the one that I (very roughly) understand, not because it is the way of approaching the topic.

Notes, Chords, Scales, Progressions, oh my!

Some definitions first. I'm by no means a music theorist, but for this post let's agree to the following definitions:

- The sound spectrum is continuous, but we subdivide it into discrete steps: notes.

- Pitch is essentially a frequency of a sound. For example, it is agreed that the "middle A" pitch is 440 Hz.

- Sound is governed by the harmonic series. In the Western (and some other) traditions we give a sound the same name (note) every time the frequency doubles. This is called an octave.

- For convenience, we decided to divide an octave into 12 equal parts, thus giving us 12 notes in an octave. The distance between these notes is a semitone.

Sidenote: This is actually a quite recent invention and is called 12-tone equal temperament or 12TET.

- If a set of notes is played simultaneously we call it a chord

- A scale is essentially just a set of notes (traditionally ascending in pitch).

- A key tone is the "main" tone of a scale. The center to which everything seems to gravitate towards.

Finally, knowing all that, what is a chord progression? It's as simple as it sounds: a sequence of chords, that is notes played together. In and of itself there is not much interesting about chord progressions. However, with time we noticed that some chords sound particularly "good" or "right" after some other chords. This is apparent in a lot of western classical, pop, or jazz music. A "one-four-five" is one such common progression, and a "two-five" is another. When practicing an instrument or as a starting point for some more creative endeavor like composing it might be nice to be able to generate any progression in any key and tell some program to play it, so this is what we'll try to do.

Laying out the basics

Let's start by defining our notes, there should be 12 of them.

type Note =

| C

| CsDb

| D

| DsEb

| E

| F

| FsGb

| G

| GsAb

| A

| AsBb

| B

As you can see some of the notes are named more complexly than others. The base set of note names is a sequence of C D E F G A B (think white keys of the piano). The notes in-between (the black keys) are denoted by either decreasing the pitch of one note i.e. flattening it e.g. E -> Eb or increasing i.e. sharpening it e.g. F -> F#. Eb and F# are enharmonically equivalent which means they produce the same sound.

Note: It wasn't always like this, the equivalence holds only in 12TET and historically they were different pitches (as dictated by the harmonic series), but we are now here and are stuck with this notation.

These notes form a so-called chromatic scale -> a set of all notes in an octave. We can represent it as a list.

let chromaticBase = [ C; CsDb; D; DsEb; E; F; FsGb; G; GsAb; A; AsBb; B ]

As mentioned before, the note names repeat when they double the pitch i.e. are an octave apart. We can represent it as an infinite series.

let tones =

Seq.initInfinite (fun i -> chromaticBase[i % chromaticBase.Length])

Intervals

To represent chords we can choose one of 2 approaches:

- as collections of notes

- as sort of "recipes" encoding how to construct the chord, knowing a starting point.

Representing a chord as a collection of notes is straightforward. However, complications start once you want to operate further on the chords e.g. add extensions, transpose to another key, make a minor into a major, etc. Thus, it is better, in the long run, to represent chords as relations between chord elements. Concretely, let's represent a chord as a set of distances from its root i.e. its "main note".

These distances are called intervals and were also given names. They are usually measured in semitones.

Note: some intervals function under multiple names. The name is dependent on the way an interval was created i.e. was it naturally occurring in a scale or was some other interval increased or decreased. That's why a Minor Third can sometimes be called an Augmented Second. I've included them as well as this terminology is actively used by musicians.

type Interval =

| PerfectUnison

| MinorSecond

| MajorSecond

| MinorThird | AugmentedSecond // Enharmonically equivalent in 12TET

| MajorThird

| PerfectFourth

| DiminishedFifth | AugmentedFourth // Enharmonically equivalent in 12TET

| PerfectFifth

| MinorSixth | AugmentedFifth // Enharmonically equivalent in 12TET

| MajorSixth | DiminishedSeventh // Enharmonically equivalent in 12TET

| MinorSeventh

| MajorSeventh

| Octave

| OctaveUp of Interval

Since we don't want to list all the intervals that exceed an octave, we perform a so-called "octave reduction" by introducing a recursive case of OctaveUp which means "the same interval but plus an octave".

Let's add a companion module with mappings between semitone values and interval names.

module Interval =

let rec inSemitones interval =

match interval with

| PerfectUnison -> 0

| MinorSecond -> 1

| MajorSecond -> 2

| AugmentedSecond

| MinorThird -> 3

| MajorThird -> 4

| PerfectFourth -> 5

| AugmentedFourth

| DiminishedFifth -> 6

| PerfectFifth -> 7

| AugmentedFifth

| MinorSixth -> 8

| MajorSixth

| DiminishedSeventh -> 9

| MinorSeventh -> 10

| MajorSeventh -> 11

| Octave -> 12

| OctaveUp interval -> 12 + inSemitones interval

let rec fromSemitones =

function

| 0 -> PerfectUnison

| 1 -> MinorSecond

| 2 -> MajorSecond

| 3 -> MinorThird

| 4 -> MajorThird

| 5 -> PerfectFourth

| 6 -> DiminishedFifth

| 7 -> PerfectFifth

| 8 -> MinorSixth

| 9 -> MajorSixth

| 10 -> MinorSeventh

| 11 -> MajorSeventh

| 12 -> Octave

| x when x > 12 -> fromSemitones (x - 12)

| _ -> failwith "Can't map this"

Chords

Having defined the intervals we can proceed to the definition of a chord. Since we've decided to define a chord as a combination of a root note and a list of intervals relative to this root, our chord could be represented as follows:

type Chord = { Root: Note; IntervalsFromRoot: Interval list }

Now we can introduce some functions that construct commonly used chords. Let's start with triads i.e. chords composed of three notes. For example, a minor triad would be a Root + Minor Third + Perfect Fifth.

module Triads =

let major root = { Root = root; IntervalsFromRoot = [MajorThird; PerfectFifth] }

let minor root = { Root = root; IntervalsFromRoot = [MinorThird; PerfectFifth] }

let diminished root = { Root = root; IntervalsFromRoot = [MinorThird; DiminishedFifth] }

let augmented root = { Root = root; IntervalsFromRoot = [MajorThird; AugmentedFifth] }

By having this defined we can for example construct an F#m chord like so:

let ``F#m`` = Triads.minor FsGb

Having this base we can define a set of functions that modify an existing chord by adding a specific note to it.

module Modifications =

let with6b chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = MinorSixth :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

let with6 chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = MajorSixth :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

let withMinor7 chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = MinorSeventh :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

let withMajor7 chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = MajorSeventh :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

let withDiminished7 chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = DiminishedSeventh :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

let with9b chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = OctaveUp(MinorSecond) :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

let with9 chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = OctaveUp(MajorSecond) :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

let with9s chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = OctaveUp(AugmentedSecond) :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

let with11 chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = OctaveUp(PerfectFourth) :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

let with13b chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = OctaveUp(MinorSixth) :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

let with13 chord = { chord with IntervalsFromRoot = OctaveUp(MajorSixth) :: chord.IntervalsFromRoot }

This, in turn, allows us to finally construct tetrachords, that is chords composed of four notes. Triads and tetrachords are the most common types of chords in popular music like pop and jazz, so our progressions will use those.

module TetraChords =

open Modifications

let seventh = Triads.major >> withMinor7

let minorSeventh = Triads.minor >> withMinor7

let majorSeventh = Triads.major >> withMajor7

let halfDiminished = Triads.diminished >> withMinor7

let diminished = Triads.diminished >> withDiminished7

let minorMajorSeventh = Triads.minor >> withMajor7

Here's how you would construct an F#maj7 chord:

let ``F#maj7`` = TetraChords.majorSeventh FsGb

Scales and modes

Now that we have our chords we can generate progressions. While any sequence of chords is technically a chord progression, we're more interested in progressions that somehow relate to a scale and revolve around its key. A basic structure of a scale can be represented as a sequence of distances between its consecutive steps. For example, a chromatic scale that includes all notes within an octave could be represented as [1;1;1;1;1;1;1;1;1;1;1;1]. Let's define some common scales like that.

type Scale = int list

module Scales =

let major = [2; 2; 1; 2; 2; 2; 1]

let harmonicMinor = [2; 1; 2; 2; 1; 3; 1]

let melodicMinor = [2; 1; 2; 2; 2; 2; 1]

For completeness' sake, we can note that the minor scale is like the major scale but instead of starting on the first step you start on the fifth. This is what we refer to as modes, basically rotations of some base scale.

let private rotate steps list =

List.splitAt steps list |> fun (x, y) -> List.append y x

module Modes =

let ionian = major

let dorian = rotate 1 major

let phrygian = rotate 2 major

let lydian = rotate 3 major

let mixolydian = rotate 4 major

let aeolian = rotate 5 major

let locrian = rotate 6 major

let minor = Modes.aeolian

let getNotes key (scale: Scale) =

let indexOfRoot = Seq.findIndex (fun note -> note = key) tones

let _, notes =

List.fold

(fun (interval, notes) value ->

interval+value, Seq.item (indexOfRoot + interval + value) tones :: notes)

(0,[key])

scale

List.rev (List.tail notes)

Now we can see which notes form the F# minor scale.

let ``F# minor`` = Scales.getNotes FsGb Scales.minor

// prints: [FsGb; GsAb; A; B; CsDb; D; E]

Harmony and progressions

In western tradition scales usually have 7 steps. They are numbered using Roman Numerals and were given names that describe their role in the scale. This applies also to chords built on top of those scale steps.

type HarmonicFunction =

| I // Tonic

| II // Super-Tonic

| III // Mediant

| IV // Sub-Dominant

| V // Dominant

| VI // Sub-Mediant

| VII // Leading tone

An example progression that we are interested in would be a I-IV-V-I i.e. tetrachords built on top of the first, fourth, fifth, and first (again) steps of a scale. To build a chord on a scale we need to only use the notes that are in the scale. This means that if we are building a triad and a third from its root happens to be a Minor Third, then our chord will be minor or diminished (depending on what kind of Fifth we will get from our scale).

First, we need a function that builds a tetrachord from a given step of a given scale.

module Harmony =

// map a harmonic function to an index

let mapToScaleIndex =

function

| I -> 0

| II -> 1

| III -> 2

| IV -> 3

| V -> 4

| VI -> 5

| VII -> 6

// this converts a scale from a representation of intervals between steps to intervals to root (key).

let private getNotesWithIntervals key (scale: Scale) =

let indexOfRoot = Seq.findIndex (fun note -> note = key) tones

let _, notes =

List.fold

(fun (interval, notes) value ->

interval+value, (Seq.item (indexOfRoot + interval + value) tones, value) :: notes)

(0,[key, scale[indexOfRoot]])

scale

List.rev (List.tail notes)

// helper function to turn a scale into an infinite sequence

let private infinite (scale: _ list) =

Seq.initInfinite (fun i -> scale[i % scale.Length])

//

let buildTetrachord key scale harmonicFunction =

let scaleNotes = getNotesWithIntervals key scale |> infinite

// find the first occurence of the key note

let indexOfKey = Seq.findIndex (fun (note, _) -> note = key) scaleNotes

// find the index of the chord root and determine the root note

let indexOfChordRoot = indexOfKey + (mapToScaleIndex harmonicFunction)

let rootNote, _ = Seq.item indexOfChordRoot scaleNotes

// recursively find the first 4 stacked thirds that form a tetrachord

// the function also accumulates semitone distances to the root to determine the right interval

let rec getChordNotes start index totalInterval notes =

if List.length notes >= 4 then

notes

else

let note, interval = Seq.item (start + index) scaleNotes

let semitonesFromRoot = totalInterval + interval

if index % 2 = 0 then

getChordNotes start (index + 1) semitonesFromRoot ((note, semitonesFromRoot) :: notes)

else

getChordNotes start (index + 1) semitonesFromRoot notes

let chordNotes = getChordNotes indexOfChordRoot 1 0 [ rootNote, 0 ] |> List.rev

// convert to `Chord`

match chordNotes with

| (root, _) :: rest ->

{ Root = root

IntervalsFromRoot =

[ for (_ ,interval) in rest do

Interval.fromSemitones interval ]}

| _ -> failwith ""

Having that, building a progression is only a matter of mapping:

let buildTetrachordProgression key scale progression =

progression

|> List.map (buildTetrachord key scale)

Finally, we can build our I-IV-V-I in F# major:

let ``I-IV-V-I`` = Harmony.buildTetrachordProgression FsGb Scales.major [I; IV; V; I]

(*

Results in

val ``I-IV-V-I`` : Chord list =

[{ Root = FsGb

IntervalsFromRoot = [MajorThird; PerfectFifth; MajorSeventh] };

{ Root = B

IntervalsFromRoot = [MajorThird; PerfectFifth; MajorSeventh] };

{ Root = CsDb

IntervalsFromRoot = [MajorThird; PerfectFifth; MinorSeventh] };

{ Root = FsGb

IntervalsFromRoot = [MajorThird; PerfectFifth; MajorSeventh] }]

*)

This has created a progression of F#maj7->Bmaj7->C#7->F#maj7. If we want to create an analogous progression but in minor, it's as easy as changing the scale and we get a progression of F#m7->Bm7->C#m7->F#m7.

let ``I-IV-V-I`` =

Harmony.buildTetrachordProgression FsGb Scales.minor [I; IV; V; I]

(*

Results in

val ``I-IV-V-I`` : Chord list =

[{ Root = FsGb

IntervalsFromRoot = [MinorThird; PerfectFifth; MinorSeventh] };

{ Root = B

IntervalsFromRoot = [MinorThird; PerfectFifth; MinorSeventh] };

{ Root = CsDb

IntervalsFromRoot = [MinorThird; PerfectFifth; MinorSeventh] };

{ Root = FsGb

IntervalsFromRoot = [MinorThird; PerfectFifth; MinorSeventh] }]

*)

Bonus: let's listen to it!

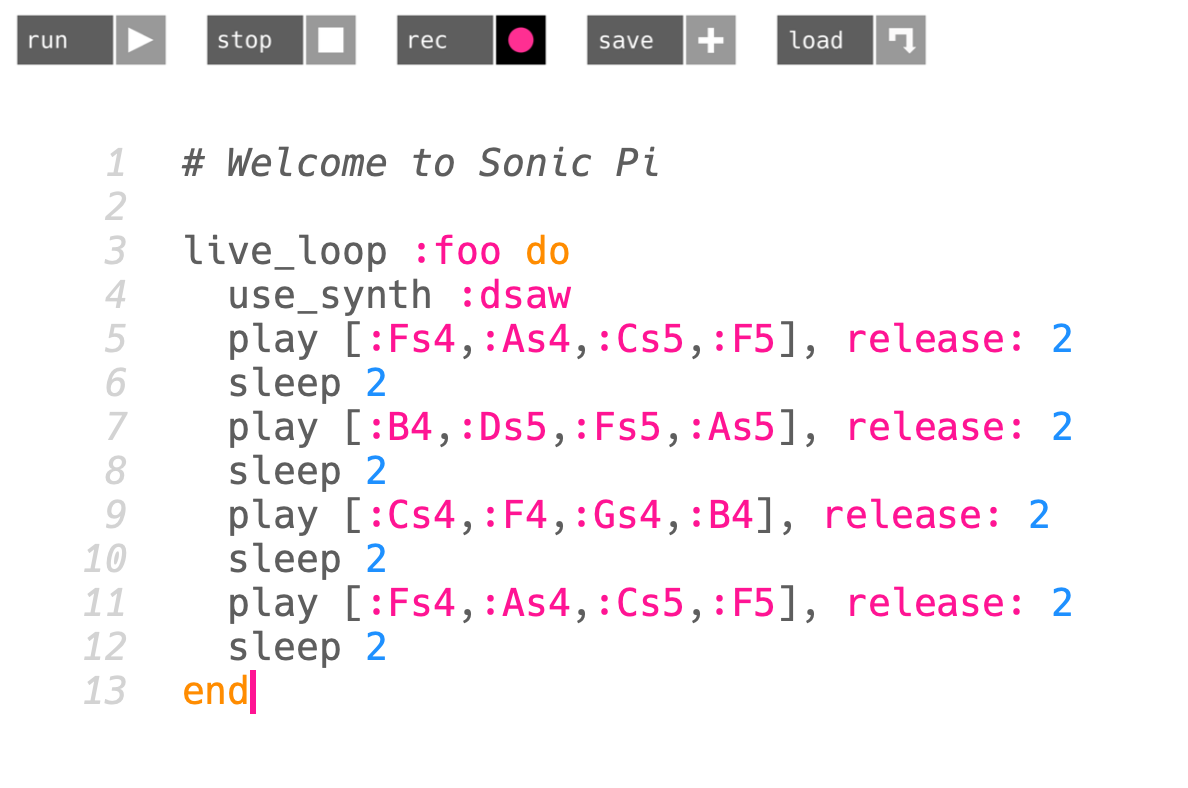

Being able to generate these progressions is a nice exercise, but unless we can listen to them somehow it is still of limited value. Here's where Sonic Pi comes in. It is a music creation tool that is code-based, which makes it a natural fit for our use case here.

In a basic scenario to play a note in Sonic Pi one has to write a play command, followed by the desired note. Additionally, we should attach a number denoting which octave we want the note to be played in. For example, the command to play the "middle A" would be play :A4. The play command can also take a collection of notes to play (play [:Fs4,:As4,:Cs5,:F5]), which is exactly what we need to play some chords! Let's add some functions to help us print a series of commands for Sonic PI based on our chord progression:

module SonicPi =

let baseOctave = 4

let toSonicPiNote (note, octaveDiff) =

match note with

| C -> "C"

| CsDb -> "Cs"

| D -> "D"

| DsEb -> "Ds"

| E -> "E"

| F -> "F"

| FsGb -> "Fs"

| G -> "G"

| GsAb -> "Gs"

| A -> "A"

| AsBb -> "As"

| B -> "B"

|> fun n -> sprintf ":%s%i" n (baseOctave + octaveDiff)

let printChord chord =

Chord.getNotes chord

|> List.map toSonicPiNote

|> fun notes -> $"play [{String.Join(',', notes)}]"

let printChordProgression stepDuration chords =

chords

|> List.map printChord

|> List.map (fun chord ->

$"{chord}, release: {stepDuration}{Environment.NewLine}sleep {stepDuration}")

|> fun chords -> String.Join(Environment.NewLine, chords)

Let's convert our chord progression to the Sonic Pi commands and paste it to a live_loop in Sonic Pi.

``I-IV-V-I``

|> SonicPi.printChordProgression 2

|> printfn "%s"

(*

play [:Fs4,:As4,:Cs5,:F5], release: 2

sleep 2

play [:B4,:Ds5,:Fs5,:As5], release: 2

sleep 2

play [:Cs4,:F4,:Gs4,:B4], release: 2

sleep 2

play [:Fs4,:As4,:Cs5,:F5], release: 2

sleep 2

*)

And here is how it sounds:

Summary

I hope you enjoyed this journey through music theory and F#. The code I wrote here is far from elegant/optimal but I found trying to fit all those concepts into code very enjoyable. I would still like to continue adding new features to make this more flexible and powerful. From the top of my head this would be things like:

- Requesting a specific type of chord for a harmonic function: for example specifying V to be the dominant seventh chord regardless of what the scale would suggest (specifying

V7instead ofV). - Chord substitutions: e.g. replace a chord in a progression with a 2-5 that resolves to that chord (jazz reharmonization)

- Reverse chord identification: a set of Active Patterns to identify whether a chord is Minor, Major, etc.

- Drop the bass note by an octave or two.

- Support chord inversions.

- and more!

You can find all the code from here in this gist. Feel free to play with it!